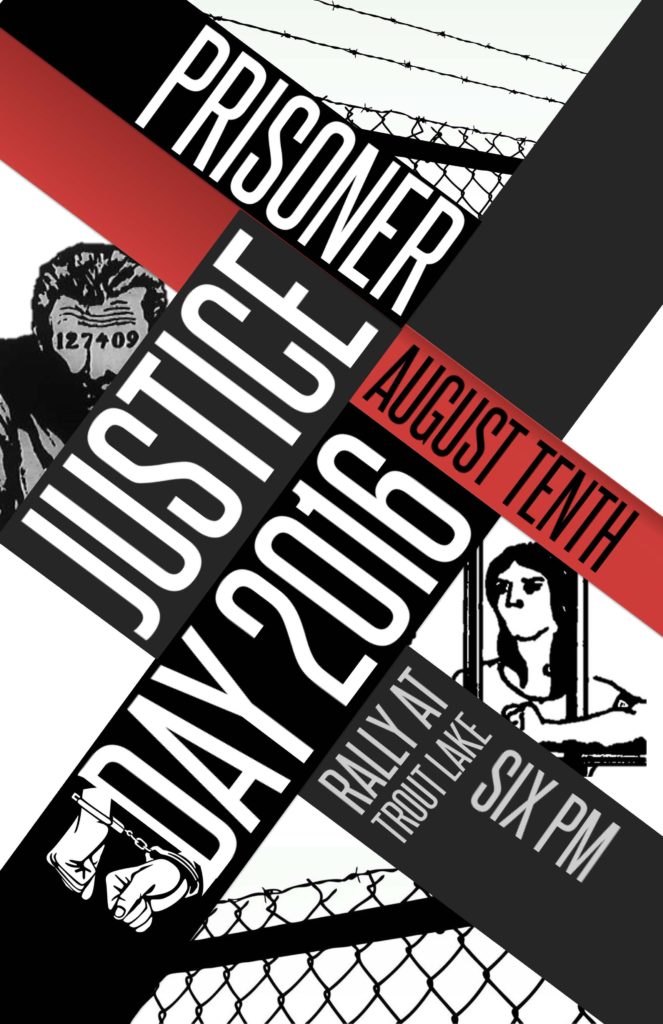

August 10th is Prisoners’ Justice Day, 41 years and counting

Prisoner Justice Day – A Short History

On August 10th 1974, prisoner Eddie Nalon slashed himself in a segregation cell of Ontario’s Millhaven prison. When other prisoners in solitary realized something was wrong they hit their emergency buttons, apparently all of them broken, and the guards failed to respond in time to save Nalon’s life. A year later, the scene repeated itself in the same seg unit. Prisoner Bobby Landers died, the emergency system remained broken. Outraged, fellow prisoners staged hunger and work strikes in memory of Nalon, Landers and all those who had lost their lives to and in prison. Since that day, Prisoner’s Justice day (PJD) has grown into a nationwide day of mourning and action on which folks inside and out make prison injustices visible and fight for prisoners’ rights. For some, PJD is also a day to agitate for an end to prisons and their replacement with community-based alternatives. For the last 40 years the Canadian prison system has banned and punished PJD activities.

Prisons are inherently violent, a fact highlighted by Nalon and Landers’ preventable deaths. The 1970s was an era of prison reform in Canada — bread and water diets, capital, and corporal (physical) punishment were abolished and new rehabilitative programming were rolled in. At the same time, a prisoner movement emerged in North America — the American Indian Movement, the Black Panthers, and other groups fought for racial justice, sovereignty, and cultural freedom inside, pointing to the continued use of prisons in a process of colonial control and genocide. Women and LGBTQ prisoners exposed the gendered and sexualized violence that marked their confinement. Prisoners rioted, occupied, formed empowerment groups and unions, wrote, launched legal cases and disrupted the everyday reality of imprisonment in every way they could. A conservative law-and-order backlash grew in response. Judges, politicians, prison guards, and others pushed for reforms to be repealed and succeeded in gaining tougher sentencing. The recent tough-on-crime agenda in Canada carries on in the spirit of this 1970s right-wing backlash.

Solitary Confinement

In the 1970s, guards were banned from giving prisoners the paddle, and so they fell back on the use of solitary confinement and other abusive practices to punish and control prisoners, as in the case of Nalon and Landers. Seeing this, prisoners and their allies argued that reform had not gone far enough. Some rallied for an end to prisons entirely, while others focused on ridding the system of its most abusive practices. They argued that solitary confinement, 23 ½ hours a day in a cell with no meaningful human contact and a ½ hour of solitary exercise in another cage was cruel and unusual punishment. Their legal challenges won some ground but Corrections Canada continued the practice by drawing up new policies with new language. The reality of solitary remained the same.

Advocates also challenged involuntary transfer, which is when a prisoner is moved between prisons, sometimes cross-country. Transfers sever ties to other prisoners, nearby family, and friends and interrupt life and routine. It is important to note that involuntary transfers and solitary confinement have been used in Canadian prisons to fracture prisoner protest by isolating, intimidating, and removing key prisoner organizers.

Grieving and fighting back

Grieving and fighting back

Powerlessness led Nalon and Landers to take their lives, just as it did in the high profile case of 18-year old Ashley Smith in 2007, and as it has for countless others. The latest stats show that one in five unnatural deaths in Canadian prison are due to suicide; half of those in solitary. This is to say nothing of life lost due to negligence, inadequate medical care, and violence, on which there is little statistical documentation. Given its history, PJD has often focused on these forms of abusive prison practice. However, it is more than that.

PJD began, as have so many social movements, from a place of grief. Like Black Lives Matter, or those organizing around Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, grief calls for action against systematized violence and oppression in its many forms: death in custody, police brutality, racist, gendered, homophobic, and transphobic violence, homelessness, poverty, marginalization, attacks on homes, lands, persons, communities, and cultures. Just like life outside, this violence shapes the prison system and people’s experiences of it in multiple ways. PJD is a day to acknowledge and combat the role of the prison and legal systems in sustaining systemic violence and inequality. It is a day to consider how we might build healthier communities and redress those actions that do actual harm, whether or not they are deemed criminal by the Canadian legal system.

We invite all readers to join us on Wednesday, August 10th in Trout Lake Park (eastern section, near the beach) at 6pm for the annual PJD speakers’ event. A fundraising event for future PJD activities will also be organized soon, stay tuned for dates and location.