Rebuilding Hogan’s Alley through the Black community’s struggle for historical justice

Hogan’s Alley was the only Black neigbourhood that existed in Vancouver’s history. Its official name was Park Lane, an alley that ran between Union and Prior Streets in the southwest corner of Strathcona, from the early 1900s through the 1960s. In 1972, the civic government enacted an urban renewal policy similar to those in many North American cities that are used to destroy poor inner-city Black communities and Chinatowns. In Vancouver, they took aim at both.

Hogan’s Alley was not a Black ghetto. Although Blacks constituted the majority, it was a neighborhood that was home to a diversity of ethnic communities that included Chinese, First Nations, Italians, Japanese and Black families. At its peak, the community counted approximately 800 residents. The community raised $500 to purchase a church, the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel, with a membership of 400 parishioners. Hogan’s Alley also included a number of businesses, such as Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, which was the center of entertainment and a hangout for prominent African American musicians like Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Ella Fitzgerald.

Unwanted in the white man’s province

Settling in Hogan’s Alley was convenient for Black men who were employed as sleeping car porters on the CPR, which had its terminus off Main Street. A respectable and well-paying job, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was Canada’s first Black trade union and its members provided important connection between Black communities (and their struggles) in Canada. Racism meant it was also difficult to find rental accommodation elsewhere in the city. For those fleeing Jim Crow laws and KKK violence in the post-Reconstruction Southern US, Canada was a beacon of hope. However, Canada was not a total sanctuary. Former residents of Hogan’s Alley talk about how as early as the 60s, city authorities allowed the neighborhood to deteriorate by not picking up the garbage and not repairing public amenities. They began to talk about how the city was planning to build a highway through the neighborhood. Gradually, community residents who felt unwanted began to leave. As they dwindled in numbers, resistance became difficult to mount against the dismantling of the community.

Loss of a home

When Hogan’s Alley was destroyed, the Black community lost its core. The displacement has affected the Black community in many respects. The displacement has contributed to loss of a place Black people call home. They scattered all over the Lower Mainland. Some were so disappointed that they returned to the US, others relocated to other provinces across Canada.

The loss of the community was a major psychological blow, which is still felt today. When new Chinese immigrants come to Vancouver, they can go to Chinatown and find familiar food, people who speak their language, organizations that can assist them. The same cannot be said for new Black immigrants who arrive in the city. They roam around the city, often unable to find adequate services or a place of easy belonging. The loss of Hogan’s Alley can also be seen as a reason for the young generation’s difficulty in climbing the ladder of property ownership. Parents who own their homes are able to help their children with a down payment. By comparison to other well-established communities, very few Black parents are able to do this for their children.

Righting historical wrong

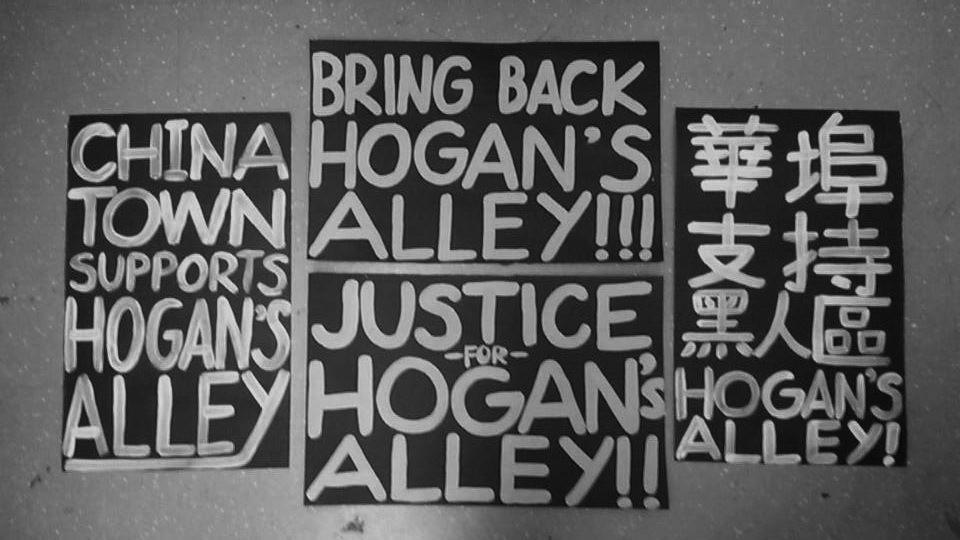

In 2015, the City Council decided that building the viaducts was not a bright idea after all, and a decision was made to remove them. The Black community wants to seize this opportunity to ensure that not only Hogan’s Alley’s cultural legacy is taken into consideration but that Vancouver learn from history and end their policies of exclusion and displacement. After 50 years the Black community is drawing together to demand reparations for the damage caused by Vancouver’s inhuman and discriminatory policies of displacement. Black residents who lost their home and cultural heritage should be compensated.

Members of the Black community have been meeting to discuss potential alternatives for the community after the viaducts are removed. Three main elements we are proposing are key to reviving the community: 1) Social housing; 2) a Black Cultural Centre where members of the community can hold cultural events, teach classes, and provide services to the community, and; 3) a Business Centre where Black-owned businesses can receive support and encouragement.

At the launch of this year’s Black History Month, Mayor Gregor Robertson acknowledged the injustice caused by the destruction of Hogan’s Alley some fifty years ago. But the possibility for justice will not come from above. Justice will be built on the solidarity between the Black community, First Nations, Japanese, Chinese and the diverse low-income community in the Downtown Eastside. Reparations will not be measured only by what happens when the viaducts are removed, they should be measured in terms of Canada’s investment in future generations to enhance the quality of life for all our communities, without sacrificing the needs of any, as a way of repairing the injustice caused by white supremacist policies against people of colour.