Liberation, Decolonization, Gacaca – Reflecting on the Rwandan Genocide, 24 Years Later

A Rwandan proverb says; “God sleeps in Rwanda.” But on the evening of April 6, 1994, God was so disgusted with the mayhem that was happening in the country that they decided to sleep elsewhere. The plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi returning from the Arusha peace talks accord was shot down as it prepared its landing at the Kigali International Airport. The death of Rwandan president Habyarimana triggered the beginning of a genocide that had been planned months in advance. In 100 days, more than a million people were slaughtered for no reason other than the fact they were born Tutsi or moderate Hutus who refused to buy into the ethnic cleansing ideology.

The persecution of the minority Tutsis in Rwanda was born of foreign intervention, through Franco-European colonialism, starting during the time leading to the independence of the country in 1962. From 1955, a wave of Pan Africanism swept through Africa and Rwanda’s King Mutara III Rudahigwa joined Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana and other African leaders who called for the end of colonial rule. The Belgian colonial power didn’t take demands for decolonization kindly. Belgium turned the tables and sided against the minority Tutsi ethnic group with the majority Hutu that it had undermined up until then.

The result of Belgium’s maneuvers was mass violence against Tutsis. In 1959, the violence against the Tutsi focused on killings and misappropriation of Tutsi property. In 1994, the Hutu plan to exterminate Tutsis was driven partly by the logic that Hutu extremists spared the lives of children in 1959 and now the same children had returned to cause trouble. Hutu anti-Tutsi extremists were confident that they could easily decimate 14% of the population and the international community wouldn’t be bothered by what happens in a small impoverished African country. They vowed to eradicate the entire ethnic group so that in the future, children would ask their parents: “Mom, Dad, what does a Tutsi look like?”

After 1994, the Rwandan genocide has come to mean two things. For the international community it is a symbol of the failure of non-intervention. The lesson of the Rwandan genocide for the United Nations and NATO therefore has been “Never Again,” a slogan that has underscored Canada’s “Responsibility to Protect” doctrine, and George Bush Jr.’s “Failed States” policy and justified invasions, wars, and occupations of formerly colonized countries in the Caribbean, Middle East, and Africa in the 1990s and 2000s. For Rwandans the genocide was caused by foreign intervention in the form of European colonialism, and these lessons are different. Rwandans have taken from the 1994 genocide the need to heal from colonialism, to reassert traditional methods of justice called Gacaca, and recover a sense of nationhood that refuses the hateful divisions sewn by the Catholic Church and French and Belgian colonial power.

The colonial roots of anti-Tutsi hate

Africans say that when the Europeans came to Africa, they came with a gun in one hand and the Bible in the other. They invited us to close our eyes and pray. When we opened our eyes, our land was taken and they had guns pointed at us.

To understand the cause of the genocide in Rwanda, one has to understand the role of Franco-European colonizers and the Catholic Church. In colonial days, the Church worked closely with Belgium to carry out the white supremacist agenda. The genocide of 1994 perpetrated against the minority Tutsi was the last of several killings that were orchestrated by successive Hutu governments, who used Tutsis as political scapegoats. After the United Nations brokered the Arusha peace accord to end a civil war between a Tutsi majority rebel group called the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) and the Hutu majority government, extremist elements of President Habyarimana’s regime felt that Habyarimana’s agreement to the peace deal had betrayed the country and that he should be eliminated. Plans were put in place to use his death as a trigger to ignite the genocide. After his plane was shot down, they blamed Habyarimana’s death on the RPA, and Hutu masses rose in anger to avenge the loss of their leader. The organizations that organized this anger into genocide, and the instruments of murder that they wielded, were outfitted by French colonial power. Although Belgium, not France, had been the direct colonizer in Rwanda, the office of the French president had invested heavily and intervened in Rwandan affairs, particularly in the years that led up to the 1994 genocide.

Besides providing genocidaires with infrastructure and weapons, colonialism also outfitted Rwanda with genocidal social and ethnic divisions. For 37 years, Rwandan refugees experienced humiliation and exclusion in the countries of exile. For example, in Burundi where I spent my childhood, Rwandans were the last to be hired and first to be fired. Every day, we were reminded that we didn’t belong there, even though culturally we were integrated. Rwanda and Burundi are like twins, we speak the same language and share similar cultural practices. The taunting and stigmatization drove most young men and women to pick up arms and fight for the liberation of Rwanda from anti-Tutsi forces and ideology.

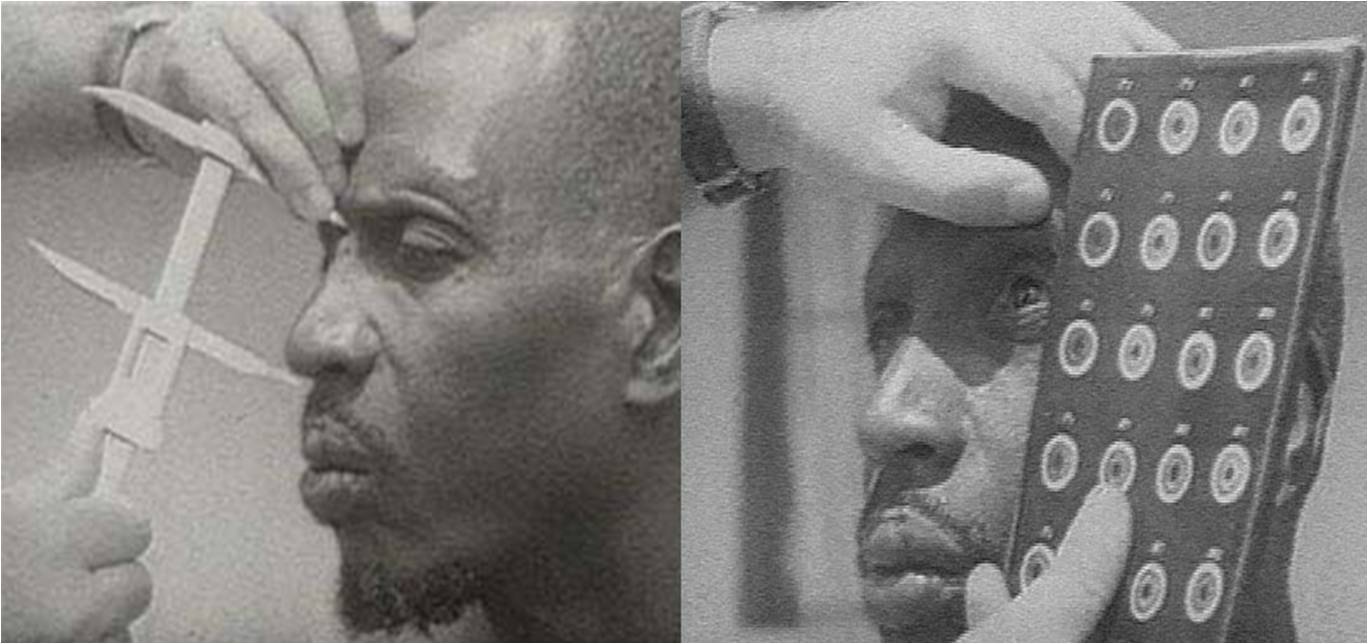

Anti-Tutsi ideology was a product of Catholic Church propaganda, and also an instrument of colonial divide and conquer. In Rwanda, 80% of the population is Christian, two-thirds of whom are Roman Catholics. Human rights activist Gerald Caplan wrote of the origins of the genocide in the Globe and Mail: “It was Catholic missionaries almost a century before the 1994 genocide who popularized the notion of Hutus and Tutsis as two distinct irreconcilable peoples, forever divided. For three decades before the genocide, the Church helped disseminate the lethal proposition that the Hutu were superior to the untrustworthy alien Tutsis.”

When you travel to Rwanda today, you see how Catholic churches across the country have become memorial sites. During the 1959 attacks, Tutsis sought refuge from anti-Tutsi violence in churches. In the 1994 genocide, churches became the killing fields. Priests invited Tutsis to come into the House of God. As soon the church was filled, they called the genocidaires to come and slaughter them.

Foreign powers made the genocide, Rwandans stopped it

Architects of the 1994 genocide had predicted that the world would not lift a finger to stop the slaughter of Tutsis in Rwanda. They believed that with the backing of France, The Vatican, and other major international players they would justify their killings as an “act of war.” While Romeo Dallaire was pleading with the UN Security Council to change the mandate of UN intervention and allow peacekeeping forces to protect innocent lives, the US was doubling down on its refusal to intervene in Rwanda. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said: “The US will not intervene in Rwanda and it will not help anyone who wants to intervene in Rwanda.”

With Albright’s statement, you can look around the Security Council table and see the impact of US power and timing. Britain was not going to oppose the American position. France was already in bed with the genocidaires. Russia had its own problems in Chechnya and China was dealing with its own human rights complications at home. The international community turned its back and allowed the genocidaires to carry on their work.

Had it not been for the intervention of the Rwandan Patriotic Army, made up of a majority of Tutsi exiles who had become seasoned soldiers through participation in anti-colonial armed struggle in surrounding nations, all Tutsis could have been exterminated as planned. At the end of June, Rwandans who had languished in neighbouring countries began to make their way back to their homeland. In Burundi, they didn’t even wait for the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) to give them transportation, they walked back.

Those who arrived in Rwanda tell the story of unimaginable devastation. Dogs were the size of calves. They were feeding on human flesh. Even today Rwandans can’t bring themselves to own a dog as a pet. The country literarily stunk. There were cadavers everywhere.

The fact that Rwandans did not rely on a foreign power to liberate their country boosted their morale and confidence. It reminded them that Rwandans are in charge of their own destiny. No foreign power can dictate to them what to do. In fact, Rwandans have since cleverly used white guilt to remind donors that they are responsible for the slaughter of a million innocent people.

Gacaca: Post-genocide Reconstruction through Decolonization

The 1994 genocide in Rwanda offers a decolonial model for post-genocide reconstruction. In the immediate aftermath of the genocide, in July 1994, Rwanda had two main priorities: to build the human capacity that will carry on the work of reconstruction, and to replace the infrastructure that was destroyed by the war. Rwanda had no Marshall Plan to help rebuild the country, so Rwandans rolled up their sleeves and began building their society one brick at a time.

Despite the devastation, Rwandans who had waited for 37 years to return home were elated at the opportunity. They knew that this was the test of their resiliency and determination to rebuild their nation. Genocide survivors still could not count on international humanitarian support because international media was tuned-in to an unfolding crisis in refugee camps in Congo, and western news audiences did not have the endurance for two African tragedies. Since humanitarian charities follow the media, it was as if they turned the lights out and closed the door for Rwandans to die.

The wounds were still fresh and anger so palpable that it was difficult to talk about reconciliation. Slowly, the country came up with a key ingredient that has been the secret to post genocide Rwanda success. They used culture as a development tool. Because we could not use the colonial judicial system to litigate the crimes of genocide, Rwandans used our restorative justice called Gacaca. Community Gacaca Courts held in public spaces offered Hutu perpetrators reduced sentences if they stepped forward and voluntarily told the courts how they killed and where they buried the dead. At first survivors were suspicious of Gacaca and felt that it was an insult, but as they learned the details of the deaths of their loved ones, Gacaca allowed survivors closure and the ability to carry out proper burials.

Since 1994, every year in Rwanda between April 6th and 15th, business hours run from 8am to 3pm in the afternoon. People meet in their villages and attend dialogue sessions where survivors tell their stories. It gives a chance for young people to learn about the painful history. At a dialogue session I attended, a woman in her fifties stood up and shared with the audience: “After I learned about the death of my siblings and parents, the pain was too heavy to bear. The perpetrator came to ask me for forgiveness. I thought about it and a voice said to me: free yourself, let the pain go. I did. The minute I forgave the perpetrator I felt all the weight that I had been carrying on my shoulders lifted. I exhaled.”

Her words summed up what most survivors were feeling 22 years after the genocide. It’s true that time has a way of healing wounds, but it also requires the venue of community, the speaking together of truth, and accountability.

Rwanda is not well endowed in natural resources like its neighbours; the country relies on its people to find solutions to major development priorities. For example, on every last Saturday of the month, Rwandans spend 5 hours doing public works. They clean the environment, pick up the garbage and spend a couple of hours discussing a variety of community policies, like family planning, housing, healthcare, security, and malnutrition.

Speaking one national language has its benefits. Rwandans use culture as a vehicle for development. For example: Gacaca is a traditional restorative justice practice based in community accountability; Umuganda is voluntary community work based on an understanding that we all benefit when each of us contributes to the common good; and Ubudehe is an instrument for helping neighbours in crisis. For example, if someone’s house burns down, neighbours gather to help rebuild the house and the victim of the fire gives them beer in exchange.

New generations undoing colonial legacies

In 2008, English became Rwanda’s official language. Although French remains one of the official languages, most young people in Rwanda don’t speak a word of French. At the 10th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide in Kigali, the French embassy raised a fuss because the ambassador was not invited to the ceremonies. The government of Rwanda responded by issuing the ambassador a 24 hour notice to leave the country. On a flight to Kigali in 2007, I recall speaking with a brother from Tchad. He said to me: “In West Africa, we admire how Rwanda stands up to France. We admire, but cannot do it,” he smiled.

For those of us who have watched the history of Rwanda unfold for decades, it’s refreshing to see that children who were born after 1994 have a different outlook on life. To the government’s credit, it has removed any mention of Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa on Rwandan identity cards and encouraged Rwandans to be proud of their shared national identity. After all, Rwandans speak the same language, share the same culture and live on the same hills. Post-genocide Rwandans have gone through a rigorous exercise of decolonizing our minds. The colonial master fueled hatred between Hutu and Tutsi and divided Rwandans into hateful camps, to maintain their colonial hegemony. Since 1994 we have come to terms with the fact that decolonization means undoing what colonialism has done.