Does Discontent City’s court defeat mean the end of legal fights for homeless rights?

“The Judge has taken away our protection”: Supreme Court decision to displace 300 people out of Nanaimo’s Discontent City spells the end of the legal defence tactic in the struggle against homeless displacement

Friday September 21st, BC Supreme Court Justice Ronald Skolrod finally – after months of waiting – released his ruling on the City of Nanaimo’s application for an injunction to break up the 4-month-old tent city on their waterfront. Over the 4 months of its existence, Discontent City has become home to over 300 otherwise homeless people; the focus of an anti-homeless frenzy that included two far right rallies led by the white supremacist gang, Soldiers of Odin; and a hot-button issue in Nanaimo’s municipal election.

Justice Skolrod’s ruling came as a surprise to residents of Discontent City, who could not imagine being sent, as one resident named Ruby put it, “right back to where we started: feeling really unsafe and out in the open without protection.” Skolrod ordered that the camp be dismantled in 21 days by police and city officials. Skolrod armed his displacement order with an enforcement clause empowering police to use whatever force necessary to break the camp.

For 2 years the Supreme Court has leaned in favour of homeless people’s rights against the power of the state to criminalize and displace, implicitly recognizing that the dominant society is causing homelessness and harming homeless people. Those days are over.

Friday’s decision in Nanaimo and the earlier decision in Saanich means that the courts have joined the politically bankrupt politicians and hateful anti-homeless property owners in irrationally calling for the expulsion of homeless people from communities. If the Saanich and Nanaimo decisions are any indication, the Courts are no longer a sanctuary from anti-homeless hysteria. The next stages of struggle against homeless displacement will have to take an adversarial approach to the courts as well as the government; we will have to face the fact that we must defend our communities with force independent of the Canadian legal and political apparatus. The alternative is to admit defeat and watch thousands of our people shrink off into the bushes to die.

Legal implications of the Discontent City injunction ruling

In the past, Judges have refused City injunction applications based on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms test of the “balance of convenience”. The balance is between homeless people’s right to “security of the person and property”, which they find in tent cities, versus the relative public nuisance and violations of property rights caused by tent cities. Previous rulings found that the “balance of convenience” rested with the life safety concerns of homeless people over what they found to be the more minor nuisance concerns of surrounding business and property owners etc. For example, in the court injunction against Anita Place tent city in Maple Ridge (which never got to go to trial) the Judge indicated that he did not see anything serious or credible in the nuisance claims of surrounding communities, but did see the life-safety concerns of homeless people as serious.

Two weeks ago in Saanich, the Supreme Court avoided this Charter question by ruling that homeless people’s rights to security are better protected by a previously established right of homeless people to find security of the person in parks on a night-by-night basis than in a tent city. The Saanich judge found that homeless people were less at risk of fire danger in night-by-night camping in parks than in a more permanent tent city. Based on this finding, he granted the injunction to dismantle Camp Namegans, effectively sentencing over 100 homeless residents to the insecurity and harms of daily displacement.

Justice Skolrod also decided that Discontent City creates dangers for homeless people, but this was an afterthought in his ruling, which focused more on the nuisance that he found the camp poses to business and property owners. In this case, Judge Skolrod took the nuisance concerns of surrounding community very seriously and, in doing so, disregarded the life-safety concerns of homeless people.

At a news conference responding to the ruling, Discontent City’s lawyer Noah Ross explained:

The judge found that there were some harms associated with a concentration of homeless people being in camp. He found that those harms outweigh the benefits of being in camp, the sense of security, benefits like a place to safely store belongings, a more secure place to build a base of your life from. We are very disappointed about that because the harms from homelessness existed before the camp was here. The harms were not created by camp, the camp exists to combat those harms.

Nuisance worries trump homeless lives

To make the leap to the ruling that public nuisance worries carry priority over homeless peoples’ lives, Skolrod characterized public nuisance complaints about the camp as “crime” and safety matters. Skolrod found that although there is always crime with poverty, the tent city has made crime worse in the immediate area. His ruling relies on police and community affidavits for this claim, not hard data.

Crime historian Eric Monkkonen has established that increases in police attendance and calls to police are not indicators of increases in crime. He says such evidence points to an “arrest wave” not a “crime wave” – resulting from increased police and community scrutiny to a stigmatized population, not from actual documented increases in crime. A young woman resident of camp since its early days named Ruby explained, “There hasn’t been an increase in crime, there has been an arrest increase. There’s more officers around here and they get called more, but that doesn’t mean crime has gone up. It’s an arrest increase, not a crime increase.” This ruling does not stand up to objective critique, suggesting Skolrod has a bias in favour of police and property owners and against homeless people.

Similarly, Skolrod’s ruling relies on the singular reports of a fire chief that campers were non-compliant with fire safety orders. In a previous application for a fire enforcement order, Skolrod found this fire chief’s testimony to be politicized and unreliable, but in this case, he ruled to displace the camp based on the same fire chief’s claims that campers are refusing to comply with the fire order. Camp council member Darcy Kory explained, “The City and fire department make it very difficult for us to function. I have met with fire officials and asked for fire extinguishers and other supports; they refused to give us water in the summer. The conditions they gave us to meet were impossible to meet without their support. It was a set-up.” Kory presented similar evidence to the Supreme Court but Skolrod did not address it in his ruling. He also ignored evidence provided from over 100 public health professionals who warned the Court that fire safety should not be isolated from other public health and safety concerns associated with homelessness.

Discounting homeless people’s safety

To make this ruling, Justice Skolrod had to discount homeless peoples’ testimonies about safety in camp and in Nanaimo more broadly in favour of unsubstantiated anecdotes from cops about “increasing violence” in camp. Ruby explained that she feels “one hundred percent more safe in Discontent City than in the rest of Nanaimo.” She says:

In camp here I have neighbours who watch my back and watch my belongings. Anyone who approaches my tent whether I am in it or not, if someone is coming around my tent my neighbours will check in with me and make sure I know them and feel safe with them.

We’re closely knit here. There’s that sense of community. People in homes have neighbourhood watch and that’s basically what we have here. I have neighbours who I share my tea and sugar with just like people have in houses.

That is going to change back to like it was before. Now where are we going to go? We don’t know. We’re going to go back to the streets where we started from, dispersed throughout the city. I’m not going to have neighbours following me around watching my back and my backpack.

Can the Supreme Court see homeless people?

Perhaps most incredibly, even though his ruling rested on a balance of convenience determination that is supposed to include concerns for homeless people’s wellbeing, Skolrod did not demand that the City/Province open more shelters or housing even though he acknowledges that there are more people at camp than there are shelter beds or housing. He used two arguments to support this bizarre ruling:

Firstly, Skolrod claims that although there are far fewer shelter beds than there are homeless people, some of these beds have apparently gone unused while the camp has been open. He does not ask why people prefer the camp to the shelters and implies blame or malice of intent of homeless people for not accessing these services rather than question the suitability of the services. Darcy Kory explained, “That doesn’t make any sense because we’re talking 300 people here in camp and the Judge is counting a few unused shelter beds to hold against us? The truth is that the housing we need does not exist.” Camper Melissa Burkhard added, “There are under 75 shelter beds available in the City of Nanaimo and they cannot house 300 homeless people.”

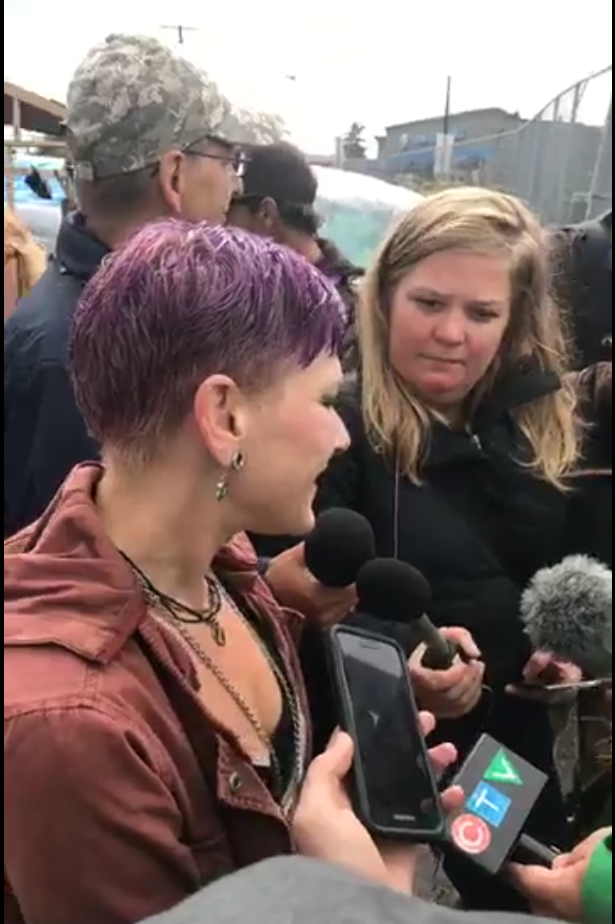

Secondly, Skolrod threw into question whether there are actually any homeless people at Discontent City at all, saying there is no proof that all the people in camp are truly homeless. Burkhart explains, “The Judge has ruled that we have 21 days to find suitable, alternate accommodations and I think just the fact that we have been here 4 months displays that there are no suitable alternate accommodations.” And organizer Sophie Welding asked, “Why is the Judge assigning the burden of proof to homeless people to prove that they exist? Why not demand the City prove otherwise? The fact that he is repeating lies from politicians shows that the Judge is biased against homeless people.”

By any means necessary: Justice after the courts

After the ruling, Discontent City’s lawyer Noah Ross noted on Twitter that “In a 141 paragraph decision Justice Skolrood did not address housing except to say that the City of Nanaimo allows people to camp in parks.” Ruby said, “We are disappointed and shocked that the judge is choosing to uphold property rights over the lives of people in Discontent City.” The overwhelming feeling in Discontent City, according to camp supporter Amber McGrath, was “sadness.” She said, “We need to stay safe and keep people together. There are shelter beds available but there are not enough for 300 people. We need affordable housing and we need it now. My personal reaction to this Court ruling is that this is absolutely disgusting and it’s a travesty. Today the Courts are sentencing people in this camp to a death sentence.”

As the news of the ruling settles, the sadness and mourning is transforming into rage. It is no secret that the courts are hostile to poor peoples’ rage. The Supreme Court judges in both Saanich and Nanaimo granted enforcement powers to the police because they noted the resistance and non-compliance of homeless campers in the camps. That does not mean that we should turn down our rage. If we can no longer use the courts as a self-defence tactic against displacement and the dangers of homelessness and extreme poverty, then the question becomes: will we defend ourselves outside the law or give in and slink away to die in the shadows of cities and towns throughout British Columbia?

The immediate challenge we will face as we develop extra-legal self-defence strategies is police and political repression. In Saanich, the Province’s police forces chased a convoy of homeless people from park to park not because they provide police escort to all homeless people, but because they were trying to break up our self-organization. Organizers in Victoria who support Camp Namegans are facing pressure at their jobs, as right wing trolls and government agents attack them and try to have them fired. And on the radio the day after we organized a pressure campaign targeting the BC NDP government that was persecuting the Namegans homeless, Premier Horgan launched a textbook right wing smear campaign, claiming the homeless were being used by radical activists. This repression is intimidating, but, paradoxically, we must realize that it is actually a sign that the NDP government and the various Municipalities we are fighting are weak and unable to maintain their rule without naked force.

Our task in the days ahead is to deepen the political crisis being experienced by the Provincial and Municipal governments that are failing to stem the growing tide of homelessness. In Saanich, Camp Namegans tent city was displaced, but it was not broken. The camp has found some needed respite on the edge of town in a licit campground, which is a bit of a retreat – but it is significant that they have not managed to scatter the radical homeless community in Saanich because the state pulled out all the stops to break us. We need to learn from the experience of mass police mobilization and repression in Saanich when we plan our responses to displacement efforts in Nanaimo and Maple Ridge, and we cannot afford to be naïve about the legal rights that provided us some protections in the past. Those days are over.

The NDP government, the Courts, and property and business owning classes in BC have reconciled themselves to a new truth – that mass homelessness is here to stay. The Supreme Court rulings in Saanich and Nanaimo have relieved governments of the responsibility to house the homeless, and are refusing to allow homeless people to shelter themselves in tent cities with the prospect of that housing on the horizon, instead prescribing city parks as permanent night-by-night remedy to the dangers and constant displacement of homelessness. Our movements can overturn this status quo only if we recognize it and respond accordingly: breaking with the NDP as an agent of bosses and landlords in our justice movements, and also breaking with civility, the bonds of legality and Canadian politeness, using any means necessary to defend our people in this struggle that is life-or-death for thousands of Indigenous and working-class people in our communities.